Hemorrhagic Bowel Syndrome: Are Your Highly Productive Cows at Risk?

HBS expert shares five tips to keep the deadly syndrome at bay.

Dr. Scott Bascom vividly remembers the first time he heard of hemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS). It was 2003, and he was listening to one of the founders of OmniGen® deliver a presentation on the relatively new bovine intestinal syndrome. Dr. Bascom was struck by the bloody gut images and the apparent randomness of incidence, and he hoped that he’d never see it firsthand in his clients’ herds. But five or six years later, while doing nutrition work at a Wisconsin dairy, he witnessed several high-producing cows die, with no clue other than bloody feces. The culprit? HBS.

Now as an executive technical services manager for Phibro, Dr. Bascom believes awareness of HBS continues to increase. As producers improve their levels of management and performance, it has become a bigger crisis to have a cow die suddenly and unexpectedly. “For the most part, U.S. dairy farms are incredibly well managed,” he says. “Producers keep their animals healthy and productive, so it really catches their attention when an animal dies. They are heavily invested in the well-being and care of their cows, so when one gets sick, it’s a very big deal.”

Sometimes referred to as “sudden death syndrome,” HBS tends to affect cows in the early part of their lactation — the time when they are most productive. In fact, Dr. Bascom says that it’s not uncommon for a cow to produce 150 pounds of milk right before succumbing to HBS. “That’s a classic HBS symptom and shows why we don’t see it coming,” he says. “It’s not like she was sick for weeks and we couldn’t get her back on track — she was doing wonderful yesterday and today she’s dead.”

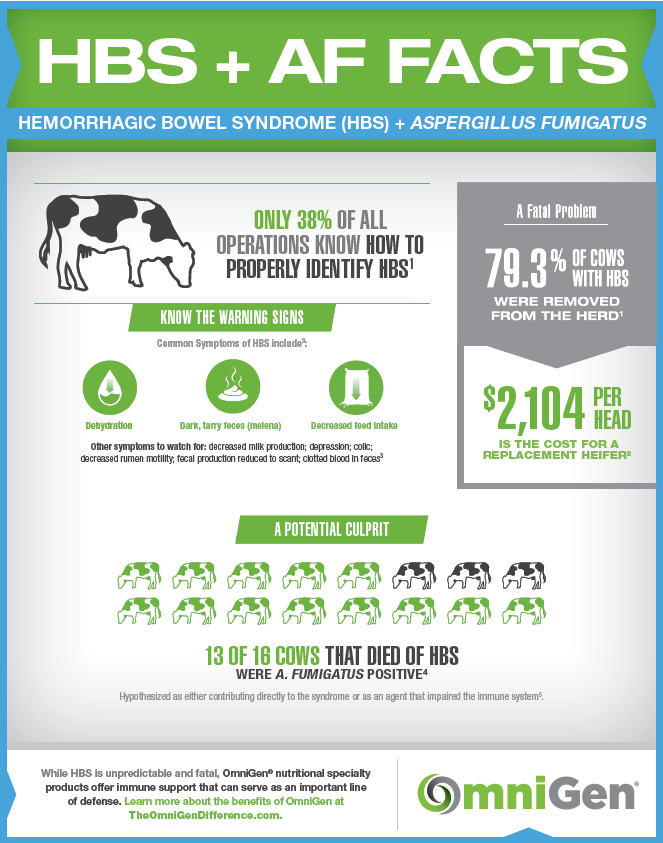

This element of surprise explains why 85% of cows that contract HBS are expected to die from it.1 There’s no effective way to treat it, and since it cannot be recreated in a lab setting, research is limited. As a result, prevention is key to thwarting this deadly syndrome.

While HBS remains to be a syndrome shrouded in mystery, we have a lot more information today than we did when Dr. Bascom first heard of the condition. For instance, 13 out of 18 cows that die of HBS are Aspergillus fumigatus (AF) positive,2 which illustrates a correlation between the ubiquitous fungus and the syndrome. And while it’s impossible to eliminate the presence of A. fumigatus, Dr. Bascom says that producers can act to reduce its occurrence — and the likelihood of HBS taking hold of their herd.

Five Ways to Protect Your Herd from HBS

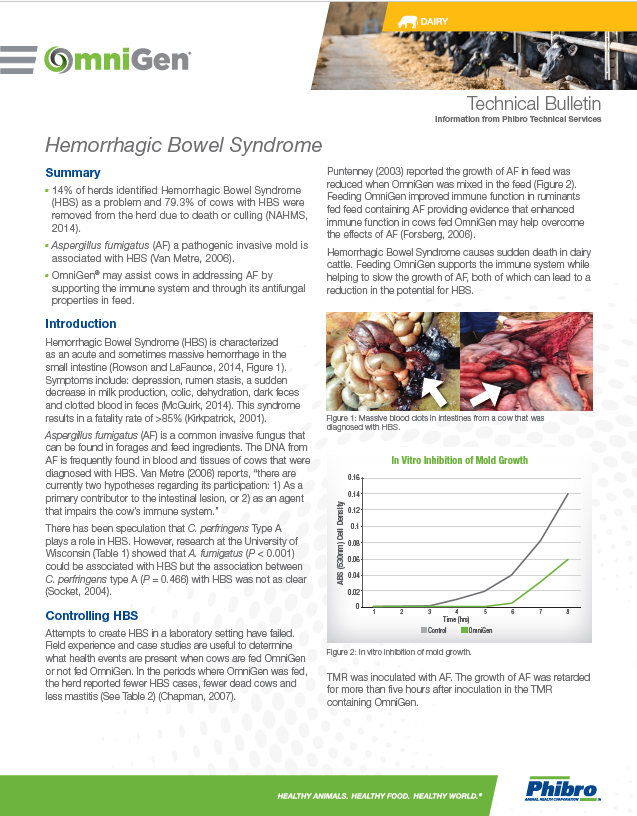

1. Feed “clean.” Reduce exposure to fungal contamination, including A. fumigatus, which has shown a statistically strong relationship to HBS. Producers should pay close attention to forage and feed quality and manage these feeds to limit fungal growth. By feeding cows “clean,” they are subjected to a lower level of A. fumigatus and a lower level of mycotoxins. Purchase commodity feeds from a reliable supplier and store the feed ingredients in a dry environment, as wet conditions are conducive to the growth of fungal organisms.

2. Reduce stress. While certain stressors, like calving, are inevitable, the stacking of multiple stressors can increase the likelihood of immune suppression —and that makes cows susceptible to several issues, including A. fumigatus and HBS. So, manage the stressors you can control to offset those you can’t. Use pens with plenty of room so that cows are not overcrowded. Ensure cows have plenty of opportunity to eat and sleep and keep them relatively free of dirt and manure. Control heat stress and make stalls comfortable places for cows to sleep and lie in.

3. Remember that knowledge is power. If you suspect that A. fumigatus might be posing a threat to your animals, have your feed tested for AF. You can also test a blood sample from cows to determine the level of AF exposure. If an animal dies unexpectedly, it’s a good idea to conduct a necropsy to determine the cause of death — and to rule out or confirm HBS.

4. Support a healthy immune system. Feeding OmniGen has been shown to increase neutrophil L-selectin. Cows with higher levels of neutrophil L-selectin are more likely to have a healthy immune system. While this is important year-round, Dr. Bascom says it’s imperative during the time a cow is most likely to experience stress — from dry-off through peak lactation.

5. Seek expert support. Because HBS is relatively rare, many dairies don’t have a high awareness of it until it’s on their operation. Phibro has the latest information on the deadly syndrome and can test tissue samples collected during a necropsy. A Phibro Stress Assessment is also a great way to evaluate for the presence of 11 different stressors, to help reduce stress and optimize herd health and performance.

After several years of studying HBS, Dr. Bascom is still struck by the disparity between proper management and HBS. “I still sometimes perceive that I will get to the dairy and spot a glaringly obvious management issue, but the opposite is often true,” he says. “HBS can be found amidst incredibly well-managed situations — it’s found where producers are doing most everything right.”

Despite that observation, he sees reason for optimism.

“Dairy producers need to be aware of HBS, but it’s not something they need to worry about every day,” he says. “By reducing stress, limiting exposure to A. fumigatus, testing feed and feeding OmniGen, this is an issue we can manage — and that should keep it from becoming too much of an ordeal on most dairy operations.”

1USDA, 2014. Dairy 2014 Health and Management Practices on U.S. Dairy Operations.

2Van Metre, D. C. and R. J. Callan. 2005. Western Dairy News: Research Progress in Hemorrhagic Bowel Syndrome. Colorado State University; University of Colorado.

OG050522GLB ©2022 Phibro Animal Health Corporation. Phibro, Phibro logo design, Healthy Animals. Healthy Food. Healthy World. and OmniGen are trademarks owned by or licensed to Phibro Animal Health Corporation or its affiliates.

Dairy Cattle Products

How Feeding OmniGen® Can Bolster Your Dairy Cattle’s Immune System to Better Defend Against Challenges.

OmniGen Green is Organic Material Review Institute (OMRI) listed.

OmniGen Green is Organic Material Review Institute (OMRI) listed.